JAMES COYNE: Bouncers and concussion subs are a hot topic, but short-pitched bowling is part of the game and batsmen are better protected than ever

Poor Will Pucovski was ruled out of the ongoing fourth Test against India, although it wasn’t for the reasons that were feared earlier in the Australian summer.

Pucovski, debuting for Australia in the third Test at the SCG, hurt his shoulder diving at midwicket – the latest injury to halt the international career of the promising young opening batsman from Victoria.

There is concern about the number of blows to the helmet he’s been copping at the tender age of just 22. The latest came in the warm-up game for Australia A against the Indians, when Pucovski got down on one knee and tried to pull Kartik Tyagi from off stump, only for the ball to clang off the top of his helmet.

The net result of Pucovski’s repeated concussions isn’t yet known. “The odds are [the concussions] won’t destroy his life, but there is a chance they will,” said Chris Nowinski, a professional wrestler-turned neuroscientist who has been a prominent figure in tackling the concussion crisis in US sports.

“We just can’t quantify that risk and we can’t quantify the additional risk of one more concussion that could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.” Hence why Pucovski was left out of the first two Tests of the series as a precaution.

Cricket has been taking note of the risks of head injuries for some years now – how could it not after the unspeakable fatality of Phillip Hughes in November 2014?

Helmets are constantly improving in quality and concussion substitutes have been possible in all international cricket since July 2019 – just in time for Marnus Labuschagne to become the first replacement, in those scary few moments after Steve Smith was felled by a short ball from Jofra Archer in the second Test of the Ashes at Lord’s.

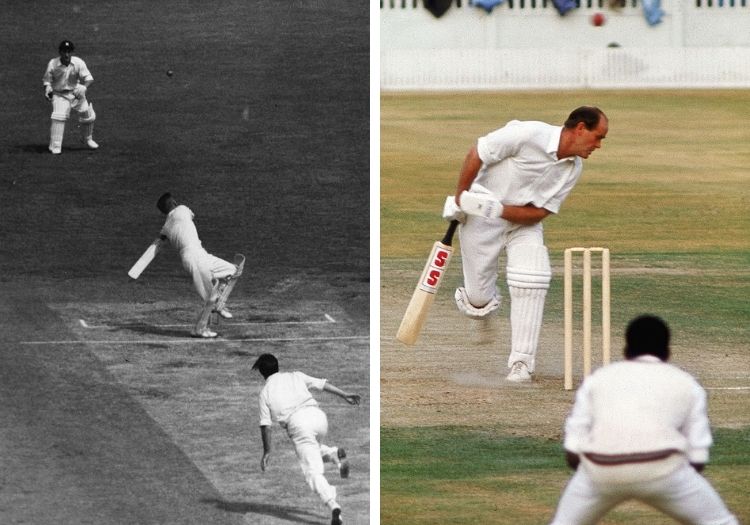

Left: Australia's Wally Grout goes hard at a short ball from Fred Trueman; right: Brian Close gets out of the way

As with most new regulations there are complexities around the practical use of concussion subs still being ironed out by the ICC.

But the frequency of head injuries has led Malcolm Knox – the highly-respected cricket writer for the Sydney Morning Herald – to argue for the bouncer to be banned entirely: “It will hurt cricket to lose the bouncer, but the bouncer is hurting cricket more. Twenty years from now, we will be wondering how the practice of aiming a projectile at a player’s head was allowed to go on so long.”

We shouldn’t scoff at a suggestion made with safety in mind, and cricket does find a way of adapting to change.

But surely this would remove one of the most challenging aspects of the game to the point of making it unrecognisable, and nowhere near as good. We may as well kiss goodbye to meaningful Test cricket in several countries, most obviously Australia.

Besides, it’s worth remembering that there was a game before helmets. Just try watching any cricket before 1978 or 1979 and the shock factor of seeing batsmen playing genuine fast bowling without a helmet and an armguard. The introduction of helmets was a big a revolution in the playing of the game as anything.

Those of us who even now don’t generally wear helmets in club cricket – I’m one, though I do put one on for the quicker bowlers at my level – are well aware of the generational sea-change on this subject: the mixture of half-concern, half-disdain from some of the younger opposition fielders when you walk out there with something so old-fashioned as your cap on.

As with so many changes in cricket, Packer accelerated it. The almost unfettered bouncer barrage in the first season of World Series Cricket, in 1977-78, led the English batsman Dennis Amiss to don a motorcycle crash helmet.

Early the following year Graham Yallop, captaining Australia minus the defected Packer players in the West Indies, wore a similarly adapted motorcycling helmet, and was booed by the crowds for his weakness.

By the second season of WSC the first custom-built cricket helmets were being manufactured, and the New Zealand batsman John Wright remembers them arriving from Australia midway through the 1978-79 home series against Pakistan.

Most first-class batsmen gleefully snapped them up, and soon couldn’t imagine life without them.

OPINION FROM THE CRICKET: The latest from our writers

Pat Pocock, the former England off-spinner, who did nightwatchman duties for most of his Surrey and England career, says: “It was chalk and cheese before and after helmets. Even hockey goalkeepers had something on their heads for years before. There were helmets for racing drivers. But nothing for us cricketers.”

It does beg the question: what about all those batsmen (and bowlers) who were hit on the unprotected head by cricket balls, and the damage they may have sustained? Hopefully someone somewhere is doing some medical research on the subject.

Some batsmen, though, took time to be convinced, believing that helmets slowed down a batsman’s reaction time. Viv Richards was said to never wear a helmet, and speaks of the pride of facing the fast bowlers in that maroon West Indian cap, plus feeling he could see better without the helmet enclosing him. He even shunned the mouth shield made for him by his dentist.

But it seems that Viv was a little more choosy about his Somerset cap, as Pocock attests.

“Viv says he never wore a helmet – well, I saw him wear a helmet against Sylvester Clarke on more than one occasion. I don’t know what happened in the inter-island West Indian games, but I saw it myself at The Oval.”

Richards possibly considered Sylvester Clarke a special case – and he wasn’t the only one. Perhaps no other bowler of his era – not even Jeff Thomson or Colin Croft – was as feared as ‘Sylvers’, though for various reasons he played just 12 Test matches for West Indies. Pocock saw plenty of him, year-in, year-out at The Oval, though.

“No cricketer the subject of such intense discussion as Sylvester Clarke,” says Pocock. “When I went on my last tour with England, to India in 1984-85, 50 per cent of the chat behind the scenes must have been about Sylvers. He was the most feared bowler in the world.

“Like many others it was the bowlers with the awkward actions I struggled with – Jeff Thomson, Colin Croft, Sylvester Clarke – and I did have to face him in the nets sometimes! Michael Holding and Malcolm Marshall had lovely actions and you could pick them up a little bit easier.

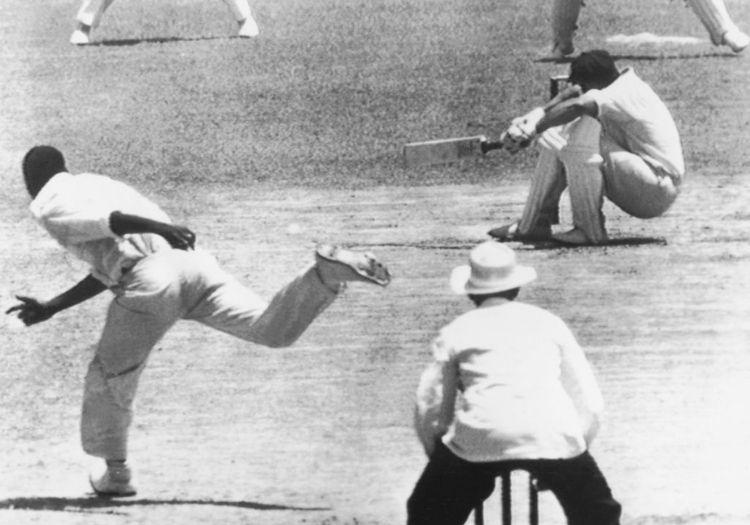

Norman O'Neill of Australia sits down to avoid a bouncer from Wes Hall of West Indies

“There were whispers about Sylvers’ action, because it was so whippy and unusual. But he had a double-jointed shoulder. Dickie Bird told me there had been a study of several fast bowlers and Sylvers came back as one of the straightest arms of all.”

Luckily Clarke was on Pocock’s team most of the time, but he had plenty of experience of facing the quick bowlers.

“Nightwatchman is supposedly the role you perform when you first come into the side but I ended up doing it for years at Surrey and when I occasionally played for England.

“Doing nightwatchman when the bowlers were fresh at the start of an innings wasn’t great. You knew they could throw everything at you in that short period, then come back the next day – or not, if it was the rest day!”

Most of Pocock’s nightwatchman duties were before the introduction of helmets. He first played for England on the West Indies tour of 1967-68, and copped a few blows on the shoulder from Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith.

He was picked against West Indies for the home series of 1976, in that blazing summer of bone-dry pitches and Tony Greig’s “grovel” comment which fired up the West Indian fast bowlers even more.

Pocock says: “In 1976 I went out and did nightwatchman against West Indies without a lid on. And, to be honest, they did bounce tailenders more than other teams did – I think mostly because they just had the fast bowlers and the capability to.

“I was used to going out with a cap for just a bit of extra protection, but it didn’t make much difference, that bit of cloth. You can see why Sunil Gavaskar and Mike Brearley came up with those peculiar skull caps under their cap.”

In the first innings of the 1976 Lord’s Test, Chris Old and Derek Underwood – both bareheaded and without armguards against Andy Roberts and Michael Holding – had freed their arms to add a fifty partnership.

THE CRICKETER'S FEATURES VAULT: Long reads, big interviews, great stories

In came Pocock, with no more than a cap to protect his head, but some peculiar spectacles.

“I had a slight wrinkle on the retina so the optician suggest I wear these glasses for a few matches. They didn’t seem to make any difference so I abandoned them after a while.

“I wore them the first time in a match at Lord’s, and as I walked past JT [Middlesex wicketkeeper John Murray] he said ‘What’s with the glasses, Percy?’ I said, ‘it’s because I’m deaf, mate’.”

That sort of gallows humour was needed in the next Test at Old Trafford, famous for the heartstopping passage of play when England openers John Edrich, 39, and Brian Close, 45, withstood a barrage of body blows from the West Indies quicks in the short period before the rest day. Some of the bowling was genuinely short; some of it rose up alarmingly from just short of a length and couldn’t be blamed on the bowler.

Holding was eventually warned by the umpire Bill Alley for bowling too much short stuff – as was the Law in those days. The hard and fast limitations on bouncers per over came in only in the 1990s.

“That wicket was lethal – there was no consistency in it,” says Pocock. “One flew off a length, brushed my nose and cleared Deryck Murray behind the stumps. It bounced once before it went over the rope.

“John Edrich was at the other end and at one point I said to him, ‘Andy Roberts is on, that’s a bit of light relief’. Edie turned to me and said ‘If we’re saying Andy Roberts is light relief then we’ve got problems!’”

Steve Camacho, the West Indies opener, is sent to the floor by a bouncer from England's David Brown

Pocock says the worst thing about doing nightwatchman was if you got out to a spinner: “It still sticks in my craw: The Oval in 1968 when I got out [lbw] to the off-spinner Edwin Smith of Derbyshire. I wasn’t too happy about that.”

When helmets did come in, some romantics moaned about their unsightliness taking away the beauty of seeing a batsman’s face; and certainly it’s true that, in my job putting together The Cricketer magazine, using an action shot of a non-helmeted batsman is somehow often more illustrative and evocative.

But for tailenders like Pocock, whose main job in those days was survival and protection from injury, wearing a helmet was an easy decision.

He certainly needed it on his recall in the 1984 series, when Malcolm Marshall pinned all and sundry on helmet or forearm. I urge you to seek out the Patrick Eagar photograph of Pocock flinching out of the way as Marshall smacks him on the glove at The Oval.

It was the most famous photo Pocock was in – and you can’t even see his face. He gleefully used it in his benefit brochure, along with the boast: “I can play this shot against anybody.”

As with so many changes in the game, it’s the unintended consequences that are more fascinating. Mike Selvey writes for The Cricketer’s upcoming February issue (out next week) about how batting against short-pitched bowling has changed from primarily back-foot survival to largely front-foot aggression.

How often do you see a batsman prepared to duck and weave out of the way? Even at club level, almost all feel they can take it on.

Pocock says: “Batting techniques have changed because of helmets and better pitches. You hooked only very carefully in those days.

“Tom Graveney scored 47,000 runs all off the front foot, but he was an exception.”

Amazingly, through his long and trying career at the crease Pocock remembers being hit on the head just twice.

“Once for Merton CC against Lord’s Nippers… Then later against Leicestershire. Jonathan Agnew bowled me one that flew off a length and smacked me in the visor. It would have hit me flush in the nose if I hadn’t been wearing a lid, so that was food for thought.

“After it hit me I was shaken up, but then I thought: ‘That’s rather nice, I’m not hurt!’”